Spacetime Physics, Chapter 8

8.3 Mass of a System of Particles

Energies add, momenta add, masses do not add.

Heat is a system property. Heat resides not in individual particles, but in the system of particles. Heat arises not from motion of one particle, but from relative motions of two or more particles.

The mass of a system is greater when system parts move relative to each other.

Remember that $E^2 - p^2 = m^2$.

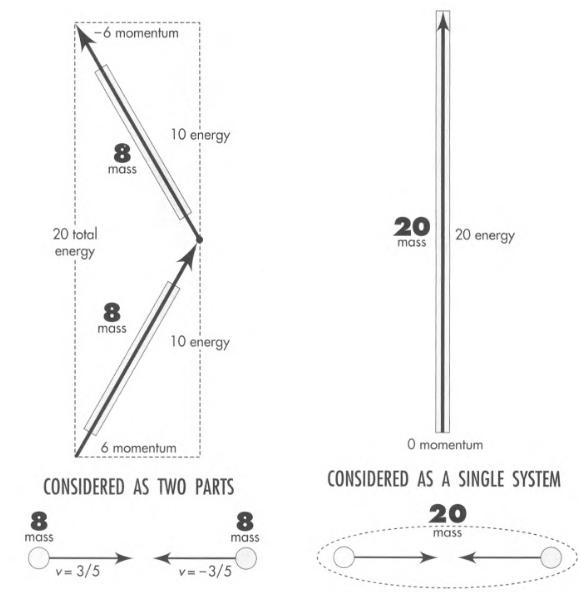

In the example below, we have two non-interacting particles, each with mass 8. Taken together as a system, their total mass is 20. $M_\text{system} = (E_\text{system}^2 - p_\text{system}^2)^{1/2} = 20$.

Ask where the extra $20 - 16 = 4$ units of mass are located? Silly question.

Ask where the $20$ units of mass are located? Good question. The 20 units of mass belong to the system as a whole, not to any part individually.

Mass of an isolated system has a value independent of the choice of frame of reference in which it is figured.

8.4 Energy without Mass: Photon

Light moves with zero aging. Photons move with zero mass.

Max Planck discovered that light of a given color comes only in quanta of energy of a standard amount, an amount completely determined by the color. These packets of energy are called photons.

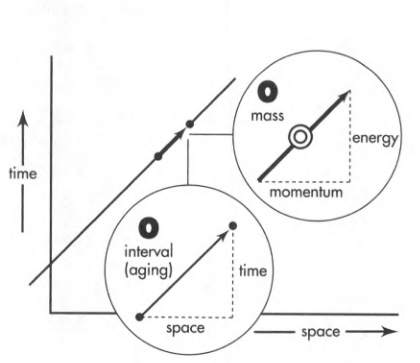

What does it mean to treat a photon on the same footing as a particle? It means we can assign to a photon an energy and a momentum, in other words, momenergy.

Photon momenergy points in lightlike direction, and has magnitude zero.

In other words, for a photon:

- Mass = 0

- Energy = Magnitude of Momentum

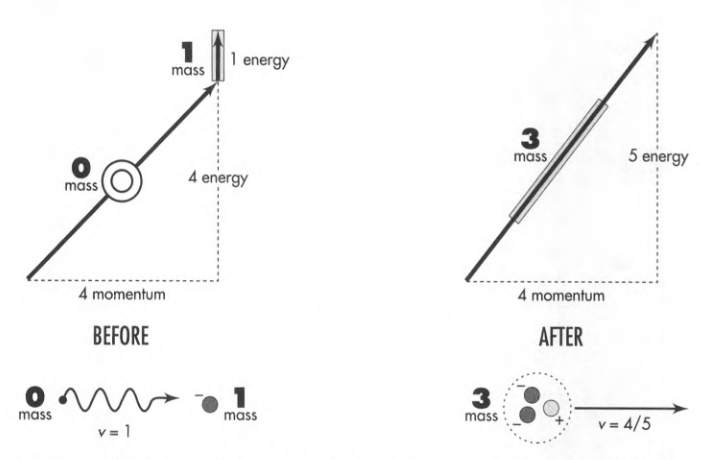

In the figure below, we see a worldline of a photon.

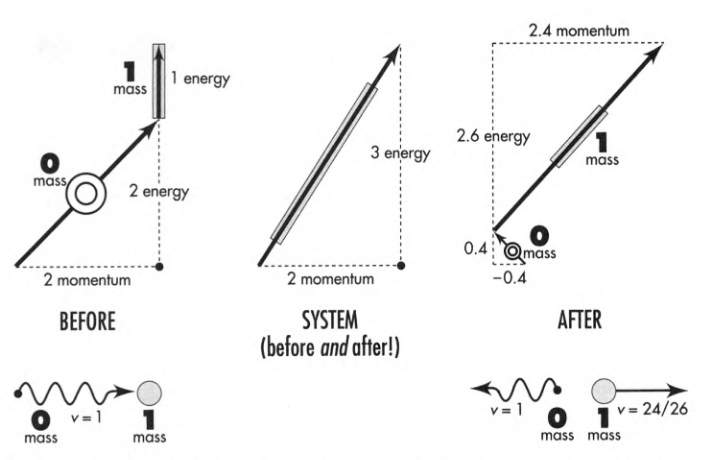

Compton Collision: The encounter between a single photon and a single electron.

We take the electron as essentially free and at rest – at rest compared to the motion it finds itself after the high-energy photon hits it.

We take the photo energy: 1.022 MeV (million electron volts). We want to express all energies in terms of electron mass, $9.11 \times 10^{-31}$ kg, or $0.511$ MeV.

Our choice of photon energy equals exactly two electron masses.

Incoming photons of this energy when encountering an electron, are scattered by the electron, sometimes in one direction, sometimes in another.

The figure shows the extreme case of back-scattering: an interchange of momentum takes place that preserves the total momentum and total energy of the system.

8.5 Photon Used to Create Mass

An electron traveling sufficiently close to light-speed can impart on its target an amount of energy 10, 100, or even 1000 times its own mass.

A photon in presence of an electron can create matter out of empty space.

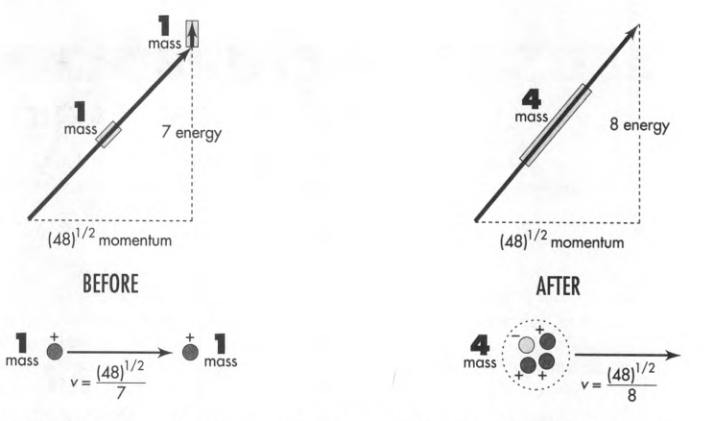

When a photon with energy equal to 4 electron masses hits an electron at rest, the photon most often scatters backward. Occasionally, however, the photon produces out of empty space a new pair of particles: an electron and a positron.

When the energy of the photon is finely tuned to about 4 electron masses, the three particles can stick together as super-light molecule called polyelectron.

(So, a polyelectron is made of two electrons and one positron.)

8.6 Material Particles Used to Create Mass

A particle of any type can carry enough energy to create particles similar to or different from itself.

Each such creation event must conserve total momenergy, total charge, and any other conserved quantities.

Figure below shows the creation of a proton-antiproton pair out of impact of a proton on another proton. The incoming proton moves with a speed of about 99% of light-speed. The target proton is at rest. The resulting three protons and one antiproton are kicked to the right at about 87% of light-speed.

The resulting particles stay together when the incoming particle has the lowest energy that can create the additional pair. This minimum energy is called the threshold energy.

The creation of a proton-antiproton pair requires a total of eight proton units of energy to create two proton units of mass.

8.7 Converting Mass to Usable Energy: Fission, Fusion, Annihilation

Three processes convert mass to usable energy:

- Nuclear fission: Splitting of the nucleus

- Nuclear fusion: Joining of two nuclei

- Annihilation: Meeting of a particle and its antiparticle

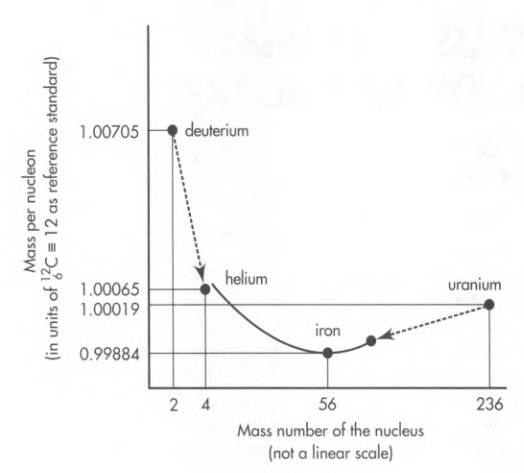

Could we split and join the same nucleus over and over again, each time releasing energy? No.

Fission occurs in the splitting of uranium, e.g. when a neutron hits a uranium nucleus:

$$ _{0}^{1}\text{n} \, + \, _{92}^{235}\text{U} \, \longrightarrow \, _{92}^{236}\text{U} \, \longrightarrow \, _{37}^{95}\text{Rb} \, + \, _{55}^{139}\text{Cs} $$

Here, the lower-left subscript is number of protons, and upper-left superscript is total number protons + neutrons.

The process rearranges 236 nucleons (92 protons + 144 neutrons) into a configuration that comes a bit closer to the most stable nuclear configuration: Iron nucleus ($_{26}^{56}\text{Fe}$).

Fusion occurs in joining of two light nuclei, e.g. when two deuterium nuclei join:

$$ _{1}^{2}\text{D} \, + \, _{1}^{2}\text{D} \, \longrightarrow \, _{2}^{4}\text{He} $$

can also be regarded as one step along the way towards the most stable nuclear configuration.

In brief, fission and fusion: both processes rearrange nucleons to get closer to the most stable nuclear configuration, decreasing the mass per nucleon. Both go from looser to tighter binding.

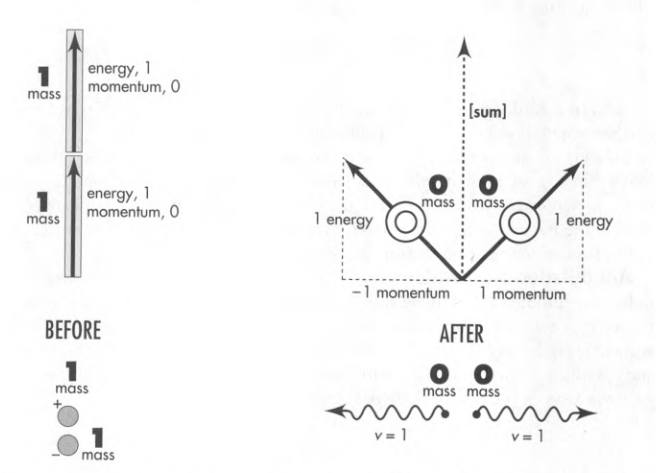

Annihilation converts 100% of matter into radiation.

$$ e^{+} \, + \, e^{-} \, \longrightarrow \, \text{2 or 3 photons} $$