Spacetime Physics, Chapter 1

1.1 Parable of Surveyors

This section talks about Daytime and Nighttime surveyors, who measure coordinates differently:

- Daytime surveyors use magnetic north and magnetic east as their reference directions.

- Nighttime surveyors use North Star north and North Star east as their reference directions.

Both use north directions in the sacred unit miles and east directions in meters.

This brings confusion when they want to compare the bounds of a property.

Then someone figures out that if k meters = 1 mile, then the following value is invariant for both surveyors:

$$ \left[ k \times \begin{pmatrix} \text{northward} \\ \text{separation} \\ \text{(miles)} \end{pmatrix} \right]^2 + \left[ \begin{matrix} \text{eastward} \\ \text{separation} \\ \text{(meters)} \end{matrix} \right]^2 $$

where both northward and eastward separations are measured from the center of the town square.

This is the principle of invariance of distance.

1.2 Surveying Spacetime

The Parable of Surveyors illustrates the naive state of physics before the discovery of special relativity.

Similar to the surveyors, physicists before the 20th century used different units to measure space and time:

- Space was measured in meters.

- Time was measured in the sacred unit of seconds.

We can use the same unit for both. Time in meters is just the time it takes for light to travel that distance. The conversion factor is the speed of light c:

$$ c = 299,792,458 \text{ meters/second} $$

Time between events: Different for different frames

In the surveyors parable, the northward readings as recorded by two surveyors didn’t differ much, since two directions of north were inclined to each other by a small angle of 1.15 degrees. At first this seemed like a measurement error.

Analogously, with the publication of Einstein’s special relativity we learned that the time between two events has different values for observers in different frames.

Two observers, two frames

John is at rest in the lab frame, while Mary is moving in a rocket ship.

- Event 1: As rocket ship passes John, a spark jumps across the 1mm gap between rocket’s antenna and a pen in John’s pocket.

- Event 2: Spark between rocket’s antenna and a fire-extinguisher 2 meters farther down the corridor.

Time lapse measurements:

- John: $33.6900 \times 10^{-9}$ seconds

- Mary: $33.0228 \times 10^{-9}$ seconds

For John the two sparks are separated by 2 meters, but for Mary they occur at the same place.

Invariance of Spacetime Interval

Similar to the parable of surveyors, here we can use the same unit for space and time using the conversion factor c, and then we can define an invariant quantity:

$$ (\text{interval})^2 = \left[ c \times \begin{pmatrix} \text{time} \\ \text{separation} \\ \text{(seconds)} \end{pmatrix} \right]^2 \- \left[ \begin{pmatrix} \text{space} \\ \text{separation} \\ \text{(meters)} \end{pmatrix} \right]^2 $$

If we calculate the interval for both events using both John’s and Mary’s measurements, we get the same value:

$$ (299792458 \times 33.6900 \times 10^{-9})^2 - (2)^2 = 98.010 \text{ meters}^2 $$

$$ (299792458 \times 33.0228 \times 10^{-9})^2 - (0)^2 = 98.010 \text{ meters}^2 $$

The invariance of spacetime interval – its independence of the state of motion of the observer – forces us to recognize that time and space are not separate entities, but parts of a single entity called spacetime.

1.3 Events and Intervals Alone!

In surveying, the fundamental concept is place. Moreover, if we have the distance between every pair of places, we can reconstruct the map. That’s all we need.

In physics, the fundamental concept is event. An event is something that has a location in spacetime. Examples of events:

- The collision between two particles.

- The flash of a light from an atom.

- Impact of a pebble that chips the windshield of a speeding car.

Every pair of observers – no matter what their relative velocity is – will agree on the interval between two events.

Wristwatch measures interval directly

We carry our wristwatch at constant velocity from one event to another. The space separation between the two events is zero in our frame, so the wristwatch directly reads the spacetime interval between the two events.

“Do Science” with intervals alone!

We can completely describe and locate events entirely without a reference frame. All we need to do is to catalog every event and list the intervals between every pair of events.

1.4 Same Unit for Space and Time

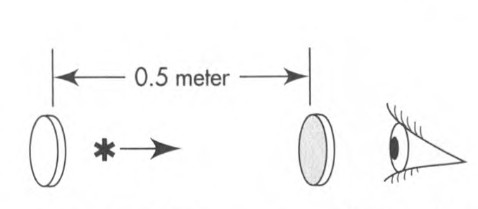

Measuring 1 meter of time:

Let a flash of light bounce back and forth between two mirrors 0.5 meters apart. Silver coating of the right mirror doesn’t reflect perfectly and lets 1% of the light through. Hence the eye receives a pulse of light every meter of light-travel time.

Official definition of a meter is the distance light travels in vacuum in 1/299,792,458 seconds.

Alternatively, we could use light-seconds, or light-minutes, … as the unit of distance.

Use convenient units, the same for space and time

- meters for describing motion of high-speed particles in the lab.

- seconds for describing events in the solar system.

- years for describing relations among stars or galaxies.